"LET'S GO QUICKSTOP", Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO)

***.5

Tarralik Duffy

June 16, 2023 - ongoing

***.5

Tarralik Duffy’s first solo show at the AGO, “Let’s Go Quickstop”, is situated in the Fudger Rotunda on the ground floor. Sitting on one of the room’s leather benches to catch my breath, I can’t help but overhear two independent critics. First, a disheveled scholar in his early twenties who marches straight to Duffy’s towering mural: a large-scale digital illustration of grocery items arranged in an 8x12 grid, each item perfectly faced like the shelves of a newly-opened supermarket. The student contemplates for a second, then remarks to his friend: “Warhol.” Shortly after, a little girl about 5 years old strolls through from the adjoining gallery. She becomes fixated on the show’s centerpiece: a large soft sculpture of a soda can, about twice her physical size. She tugs on the arm of her accompanying guardian: “Why is there a giant Pepsi on the floor?”

I didn’t interject because I try to abide by a civil social contract that precludes me from inviting myself into the conversations of others, but the scruffy man wasn’t wrong: the most straightforward, knee-jerk comparison to Tarralik Duffy’s pop art, which is the focus of this show, is the late Andy Warhol. Both artists’ work employ the immediately accessible imagery of popular commodities as kickstarters for examination—Warhol’s 1960s Campbell’s Soup cans are Duffy’s Pepsi and Red Rose Tea. But the similarities end, more or less, at aesthetics. While Warhol used his projects to outwardly critique—to dissect societal valuations of art, the boundaries between high art and low culture, the transitory nature of beauty and celebrity—Duffy approaches her subject as a deeply personal and imaginative nostalgia. The items rendered here are lifted from Duffy’s childhood in Nunavut—objects that she notes have come to permeate contemporary Inuit life. Warhol’s pop art—emerging out of the post-war consumer boom, a reaction to abstract impressionism—worked to recentre art around a depersonalized, objectified iconography. Duffy utilizes these pop art aesthetics to instead present something fundamentally opposite: a deeply personal, narrative work that prods at the presence of these commodities as dominant figures in Inuit communities.

The mural, in its colourfulness and scale, and the soft sculpture at the centre of the rotunda, with its plump and pillowy dimensions, are the main draws of this show’s illustration works and sculptural works, respectively. Around the rotunda are complementary pieces that round out the show. There is an illustration of pop, chips, and chocolate, which Duffy has deemed “the triad of Nunavut junk food” (these were also the focus of “Pop Chip Kakuk”, Duffy’s 2022 solo show at Ottawa’s SAW Nordic Lab). Duffy cites these foods as prominent choices, often consumed together, especially when shopping for taquaq—food brought along during long trips out onto the land. There is another illustration nearby, this time of a single item: Crosby’s Fancy Mollasses, which she spoke about at length for Foyer (an AGO publication):

“I have a very specific memory of the look of the packaging of Crosby’s Molasses from the 80s. When I walked in to see the installation for the exhibition, I started crying because it was like looking at the molasses on my Anaanatsiaq's (grandmother's) table. I didn't expect to have such an emotional reaction to my own work, because I’ve seen it a lot, and I've already drawn it and conceptualized it. It’s very nostalgic to me, and it took me right there. When we lived in Nunavut, we would always visit my grandmother daily, and if she made fresh bannock, we would dip it in the molasses. Usually there'd be a really messy molasses carton on the table and you pour it into a bowl. For me, the items are reminiscent of visiting my Anaanatsiaq’s house – or my mom's house. To me, they represent more than the store. I'm also a sucker for marketing – I like a well-marketed product. There's something so nice about items that have yellow, or black - I'm very drawn to things like that. They're very tied to my relationship to my Anaanatsiaq, and my mom, and visiting culture in Nunavut.”

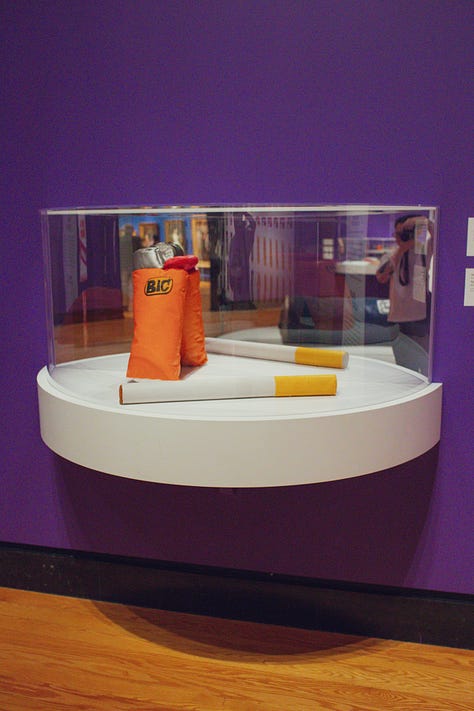

The other soft sculptures on display are held in glass. There’s a cushiony Bic lighter (Bic Lighter, 2023) next to a cigarette (Siggalii, 2023) that resembles in length a full body pillow; the pair highlights a playfulness and sense of humour in Duffy’s work (as well as a keen marketability). Next to the mural are a Klik can plushie (Klik Can, 2023) and a Pilot biscuit the size of a couch cushion (Pilot Biscuit, 2023), both made of commercially tanned leather, polyester filling, and artificial sinew; these two pieces are placed next to a plastic bag (Northern Store Bag, date unknown). These forays into soft sculpture are a newer venture for Duffy, a clever thematic extension of her digital illustrative work, and perhaps the most exciting part of the show as an indication of how her art practice is evolving (note: all the soft sculpture pieces are from 2023). Their playfulness reinforces the sense of childhood and nostalgia cultivated in this show, while simultaneously challenging notions of Inuit sculpture as strictly traditional, carving-based works.

The show culminates when, after being made comfortable by the familiarity of these everyday objects, the viewer begins to pick up on some irregularities. On her mural of grocery items, all products are rendered dutifully except for one: Robin Hood All-Purpose Flour is, in fact, Robin Hood Palaugaaq Flour. Upon close inspection, the illustrated Oh Henry! candy bar reveals a Kukuk® branding instead of the traditional Nestle®. The soda pop beneath it looks an awful lot like an original Coca-Cola, but instead the can reads: Kuuka Kuula. The “giant Pepsi” the young girl was enamoured with, sitting at the centre of the rotunda, is actually a Pipsi. This is a recurring theme in Duffy’s work: the use of Inuktitut syllabics to recontextualize these goods, and to reimagine them as products of a mainstream Inuit culture. There is a craftiness here that doubles as an evocation—what have these ubiquitous products replaced in Inuit communities, and by what methods of proliferation?

Though the dim, sparse lighting of the rotunda dulls her bright, primary colours, and despite the glass cages holding her youthful sculptures rendering them like ancient artifacts, Duffy’s work remains chiefly joyful. It emphasizes the Inuit identity as one capable of maintaining and adapting cultural traditions throughout unmitigated and disastrous circumstances and history, yet it rejects offering relief or pandering to Western audiences by continuing to invite examination. I was drawn to Duffy’s work because of our shared history with canned meats—I grew up eating Maple Leaf Vienna Sausage, which lines one of the shelves of her mural; instead of Klik Luncheon Meat, my family indulged in Spam. I think there is a whole unwritten history of these products, and how their export connects many disparate communities across the world. But as I imagine sharing a meal of perishable canned foods with loved ones, I realize that I am, in fact, just offering myself relief from the vulnerability of self-examination. As for the girl who asked about the soda pop laying knocked over on the rotunda floor? No one answered her question. They just kept walking through.